Have you just tried using a to do list?

People love to say “Have you just tried using a to do list?” as if this is a life chan revelation that you’ve never thought of. The tone is always the same. Light. Practical. Harmless. As though the only thing standing between me and a well ordered life is the purchase of a notebook or the download of an app. I have heard this line more times than I can count, and every time it lands in exactly the same place. The assumption is that I have never thought of this before, as though I have been living my entire adult life unaware that stationery shops exist. The truth is I have tried every system ever created. Every app, every notebook, every whiteboard, every project tool, every productivity method, every neatly marketed solution that promises clarity and ends in disappointment. None of them worked. Not one.

People misunderstand what we are asking for when we reach for a to do list. We are not looking for a place to write things down. We are looking for order, and for a sense of control over a world that often feels chaotic, unpredictable and full of hidden traps. We want something that will help us remember the things that slip through our fingers. Something that will help us prioritise when everything feels equally loud. Something that will protect us from the embarrassment of forgetting what we said we would do. Something that will allow us to start the day with a clear map and finish it with a sense of completion. Something that will help us feel, for once, like a normal person who has their life in some kind of shape.

That was always the fantasy for me. I imagined myself beginning every morning with a fresh page, knowing exactly what needed to be done and in what order. I imagined ending each day with tasks crossed out, a small glow of pride, a sense that I had moved my life forward deliberately rather than frantically. I imagined remembering birthdays and deadlines and appointments without last minute panic. I imagined handling the important things before they became urgent. I imagined a life where I was not constantly winging it, hoping that adrenaline would save me one more time. This is what people misunderstand. A to do list is rarely about tasks. It is about the longing for safety. For neurodivergent adults who have spent years dropping things they meant to remember, the idea of a single tool that could finally hold everything feels like salvation.

But the reality of using one has never matched the fantasy. The moment I faced the page, my mind did something entirely different. I froze. Everything I wrote down looked equally important. Everything felt urgent. Everything belonged at the top of the list. My brain could not see sequence or order. It could not tell me what should happen first. It did not feel like clarity. It felt like exposure. A list does not distinguish between a two minute task and a life changing one. It presents them all in a single vertical line, and for a nonlinear brain that is impossible to engage with. My autistic side craves structure, predictability and clear categories. My ADHD side forgets the list exists within hours, avoids it when overwhelmed and abandons it entirely the moment novelty fades. These two realities collide violently. I deeply yearn for order, and yet my executive function challenges make it almost impossible to maintain.

Apps do not help with this. Notebooks do not help with this. They rely on remembering to open them, remembering to update them and remembering they exist. For me, that is already an impossible ask. My object permanence is terrible. Anything out of sight is as good as gone. I have hundreds of notebooks with only one or two pages used, each one representing a fresh attempt at adulthood followed by a quiet collapse. I cannot read my own handwriting after a day. Apps disappear behind screens. The moment I close them, they vanish from my awareness. They become symbols of a system I will never master, artefacts of a life that is always slightly out of reach.

There was a period when I thought I had finally cracked it, or at least found something close. It happened after I started ADHD medication and began thinking deeply about what I was actually struggling with. I needed a physical solution. Something I could not forget. Something that stayed in my line of sight. Something that did not require me to remember to check it. I bought packs of Post it notes in different colours and covered an entire wall of my office with them. People called it my “murder wall” as it looked like the boards in the detective shows where all the clues are pasted with string identifying connections. To me, it felt like the first time I had ever seen my mind outside my head.

The setup was simple but incredibly deliberate. Along a horizontal line, at eye height, I placed blue Post it notes labelled with my main themes of work. Above each one I placed smaller notes for high level objectives. Below each theme, I placed yellow notes for active tasks and further below that another section for delegated tasks. I used coloured dots to mark urgency and importance. I dated every note. When I leaned back in my chair to think, my eyes naturally scanned the themes and the objectives. When I sat upright, the active tasks sat exactly in my line of sight. Delegated tasks lived below, visible but less prominent. The entire system mapped effortlessly onto my visual and spatial processing. It became more than a list. It became an extension of my working memory.

But the real magic came from how I integrated it into my day. I cleared the left side of my desk and designated it as my today area. Every morning it was empty. I was forced to scan the wall and choose no more than five tasks. This part was critical. If a task could be broken down, I broke it down. A single note that read “do compliance training” became six individual notes for each module. Breaking them down removed overwhelm and created more opportunities for completion dopamine. Once I selected my tasks, I placed them to the left of my keyboard. As I worked through the day, I would move one Post it at a time from the left side to the space directly in front of my keyboard. That was my working memory zone. If I got distracted or had to take a call, the task never vanished. It sat there waiting. When I finished something, I moved it to the right side of my keyboard. At the end of the day I transferred those completed notes to a dedicated section on the wall. On Fridays, I grouped them by theme, wrote a summary for my manager and cleared the space for the next week. The ritual mattered. The movement mattered. The visibility mattered. It worked in a way no to do list ever had.

For months, it was extraordinary. I became super organised. People noticed. I would reply to an email someone had sent me a week earlier and they would say they had forgotten they even asked. I responded to things on time. I completed my compliance training within a week of it being assigned instead of staying late on the final day. I remembered things I had previously dropped. I was achieving the fantasy of the to do list at last. I looked like a reliable, consistent, capable adult. And I will admit it felt good. For the first time I felt competent in a way that matched how I had always believed myself capable of being. It felt like I had finally cracked the code of normality.

But then something shifted, and it took me a while to see it. The system was working so well that I became a machine. A human doing, not a human being. I executed tasks with speed and precision, but I lost something essential in the process. I did not have time to think. I did not have time to imagine or to be creative. I did not have moments of wandering thought or spontaneous insight. Everything became linear and reactive. My role is not to be a task executor. My value lies in nonlinear thinking, in seeing patterns others miss, in designing systems and strategies, in deep conceptual work. The very thing that made me effective was being pushed out by the very system that made me efficient.

It dawned on me that I had built a factory. A brilliant, elegant, finely tuned factory that turned me into the least interesting version of myself. I had chased the dream of becoming a real boy, only to discover that when flawless organisation finally arrived, it was not somewhere I was meant to live. It was a costume, not a home. I shut the system down the moment I understood what it was costing me. People think ND systems fail because we cannot maintain them. Sometimes they fail because they succeed too much in the wrong direction.

What I needed was not a way to control my tasks. I needed something that worked with the grain of my cognition, not against it. And that was the turning point. When the murder wall reached its limit, I evolved. I stopped building task systems and started building systems for my brain. I created a second brain in Obsidian which is like an electronic notepad on steroids, and feels like having a private internet for my thoughts.

It changed everything.

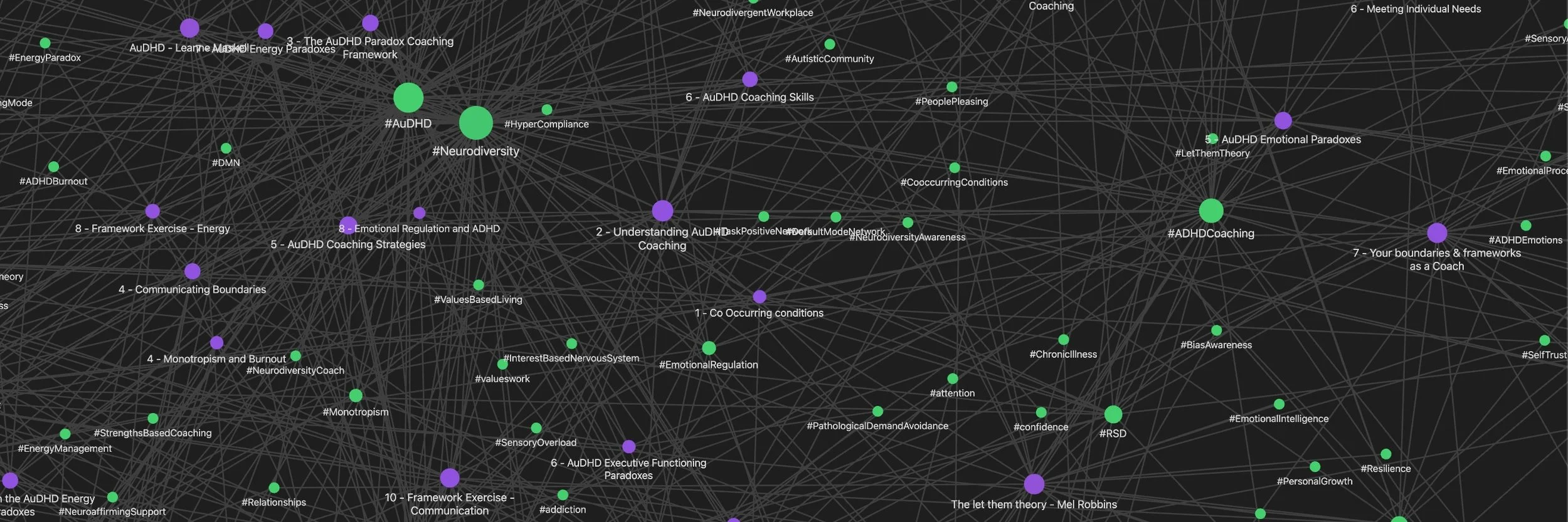

Instead of forcing myself into a linear list, I built a nonlinear ecosystem. My external brain mirrors the way my mind actually works. It is networked, branching, interconnected, alive. I no longer need to remember everything. I write it down. I store it. I link it. I use AI to automatically tag and summarise it. I let my second brain hold what my first brain cannot. Tasks are captured anywhere and surfaced automatically. Notes are summarised and indexed with my own local AI tools. Screenshots become searchable text. Every article I write is logged and summarised. Every coaching concept I learn becomes a node connected to others. I listen to books on Audible, but then get ChatGPT to generate a summary which I add to my Obsidian vault. I have scripts that run each night, creating embeddings to drive my local AI tools. I can now ask questions like “How would I handle a coaching situation like this based on my past learnings?” and receive answers derived from my own knowledge base. Nothing is lost anymore. Nothing disappears. Everything connects.

Most importantly, I no longer live in a task based reality. I live in an interest based one. The heart of ADHD is interest driven cognition. The heart of autism is structured thinking. Obsidian gives me both. It lets me follow curiosity without losing context. It lets me build knowledge without losing track of where anything is. It lets me generate linear structure when I need it without forcing me to think that way. My tasks sit quietly in the background, ready for me when I want them, but they no longer define my day. My system finally honours my nonlinear brain instead of fighting it.

It has turned the impossible to do list into something entirely different. A nonlinear representation of reality that mirrors the way my mind has always worked. And with the tooling I have built, I can now generate linear views of that nonlinear world whenever I need to, without having to store my life in a straight line.

This is what I wish someone had explained to me years ago.

If I was coaching someone on organisation, I would not start with tools at all. I would start with what their brain is asking for. Most of us come into adulthood believing that organisation is a character trait, something you either have or lack. In reality it is a relationship between your nervous system, your environment and the way information moves through your mind. I would invite them to notice the moments they feel least lost, and what their environment looks like at those times. I would ask them to pay attention to the places where their mind naturally stores things, because we all have patterns we never consciously designed but have relied on for years. Those patterns often tell us more about our needs than any app ever will.

I would ask them to explore where organisation becomes shame rather than support, and what stories sit underneath that. Most people with ADHD and autism do not struggle because they lack discipline. They struggle because the systems they were given were never designed for the way the way their minds actually work. I would help them notice whether their mind needs linear order, or spatial order, or visual order, or narrative order. I would help them see that remembering is not a moral act, and forgetting is not a personal failure. Organisation only works when it removes pressure, not when it adds another layer of self judgment.

I would also invite them to experiment with systems as living things rather than fixed structures. Organisation is not about choosing the right method and forcing yourself to sustain it forever. It is about finding something that can move with you, that adapts to your energy, your attention and your emotional capacity. For some people that means physical systems. For others it means building a digital external brain. For many it means a combination of both. The goal is not to become a perfectly consistent person. The goal is to create an environment that lets you be yourself without constantly fighting your own mind.

Above all, I would ask them to stop trying to organise themselves into a different person. Organisation should never cost you your creativity, your sense of self or the parts of your mind that make you unique. It should give you more room, not less. When you build a system that matches your neurology rather than correcting it, organisation stops being a punishment and becomes a form of grounding. It becomes a way of making space for the life you want to live, not just the tasks you need to complete.

https://obsidian.md

Willcutt, E. G., Doyle, A. E., Nigg, J. T., Faraone, S. V., & Pennington, B. F. (2005). Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biological psychiatry, 57(11), 1336–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.006

Murray, D., Lesser, M., & Lawson, W. (2005). Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism. Autism : the international journal of research and practice, 9(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361305051398

Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Sinha, R., Hetland, J., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The Relationships between Workaholism and Symptoms of Psychiatric Disorders: A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study. PloS one, 11(5), e0152978. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152978